“For those who are rethinking the core portfolio, where to begin? Finding a steady hand in unsteady markets, for starters.”

Joan Solotar, Global Head of Private Wealth Solutions, Blackstone Inc.

At the simplest level, private capital investments refer to investments made in privately held companies or assets that are not publicly traded. Over the past century, institutional and private investors alike have found that opportunities to invest in private markets can provide diversification benefits and return enhancement across a range of strategies, ranging from private equity to private debt to venture capital. While real estate and more esoteric strategies are also considered private capital investments, they are covered in other GLASfunds educational materials.

THE HISTORY OF PRIVATE CAPITAL

The concept of private capital investing can be traced back to the early days of capitalism, when wealthy individuals invested in businesses and ventures in order to generate returns on their capital. However, it wasn’t until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that private capital investments began to take on the more structured form that we recognize today.

In the early 1900s, the first private equity partnerships were formed in the United States, with the founding of firms such as J.H. Whitney & Co. and the American Research and Development Corporation. These early private equity firms focused primarily on investing in early-stage companies, and they often played an active role in the management of their portfolio companies. Over time, private equity investing expanded beyond early-stage companies to include leveraged buyouts, distressed debt investing, and other investment strategies.

Today, private equity investing is a global industry with over $12 trillion dollars in assets under management.

STRUCTURE

Private equity funds typically have a two-tiered structure consisting of general partners (GPs) and limited partners (LPs). The GP is responsible for managing the fund and makes investment decisions on behalf of the investors, while the LPs provide the capital that is invested in the fund.

GPs are typically responsible for identifying potential investments, conducting due diligence on those investments, negotiating terms, structuring deals, and managing the portfolio companies once they have been acquired. The GP is also responsible for managing the fund from LPs, typically institutional investors, and wealthy individuals. In exchange for their services, GPs usually receive a management fee that is a percentage of the total capital committed to the fund, as well as a share of the profits generated by the fund, known as carried interest.

LPs are typically given preference before the GP can collect carried interest. It’s common for LP’s to be entitled to a full return of capital and a preferred return of 8% per annum on the capital utilized for a specific deal.

LPs, on the other hand, are passive investors who provide the capital that is invested in the fund. LPs typically do not have direct control over the investments made by the fund, but instead rely on the GP to make investment decisions on their behalf. LPs are typically required to commit their capital to the fund for a fixed period, usually up to 10 years or longer.

During this time, LPs are not able to withdraw their capital from the fund, although they may receive distributions from the fund as portfolio companies are sold or generate cash flow.

The structure of private equity funds is designed to align the interests of the investors and the fund managers. GPs are incentivized to generate strong returns for the LPs, as this will increase the amount of carried interest they are able to earn. Strong returns may increase the potential that the GP can raise a larger subsequent fund and benefit from more management fees as well. LPs, in turn, are incentivized by their preference rights and prospects for attractive returns. GPs commonly receive ample flexibility to implement their strategy.

INVESTMENT ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS

In the United States, eligibility to invest in private equity is generally restricted to Accredited Investors (AI) and Qualified Purchasers (QP). An AI is an individual or entity that meets certain income or net worth thresholds, as defined by provisions in Investment Company Act of 1940 For individuals, this typically means having an income of at least $200,000 per year ($300,000 if married) for the past two years, or a net worth of at least $1 million (excluding their primary residence).

QPs are similarly defined by the Investment Company Act, but with higher income and net worth thresholds. Specifically, QP individuals must own at least $5 million in investments, or be a family-owned business with at least $5 million in investments, among other criteria. QPs classified as entities have different criteria.

These eligibility requirements are in place to ensure that private equity investments are only available to individuals or entities that can understand the risks and complexities of these types of investments and have the financial means to absorb potential losses. There are multiple definitions and criteria for individuals and entities to qualify as Accredited Investors and Qualified Purchasers that go beyond the scope of this paper. Advisors need to carefully consider each investor’s circumstances to determine if qualification requirements are satisfied.

Private Equity’s Role in Portfolios

We believe that private capital strategies primarily serve as return enhancers in a diversified portfolio. There are also diversification benefits, but this is a secondary role in our view. Private equity has exposure to the same macro and market factors as public equities, such as growth, inflation, interest rates and credit spreads. Quantitatively, diversification benefits are likely overstated given that public equity is priced intra-day by markets and most private equity funds are appraised on a quarterly basis.

However, private capital strategies can provide exposure to different return drivers that are hard to access in the public markets. For example, venture capital funds provide exposure to younger companies that have high growth potential and potentially innovative products or services.

Start-ups may account for a disproportionate amount of economic growth in the US. It is challenging to gain exposure to young, innovative companies in the public markets, but private equity funds can provide exposure to these sectors that are not accessible in the public markets. Lastly, some private strategies may seek to fulfill ESG related mandates in addition to generating attractive returns.

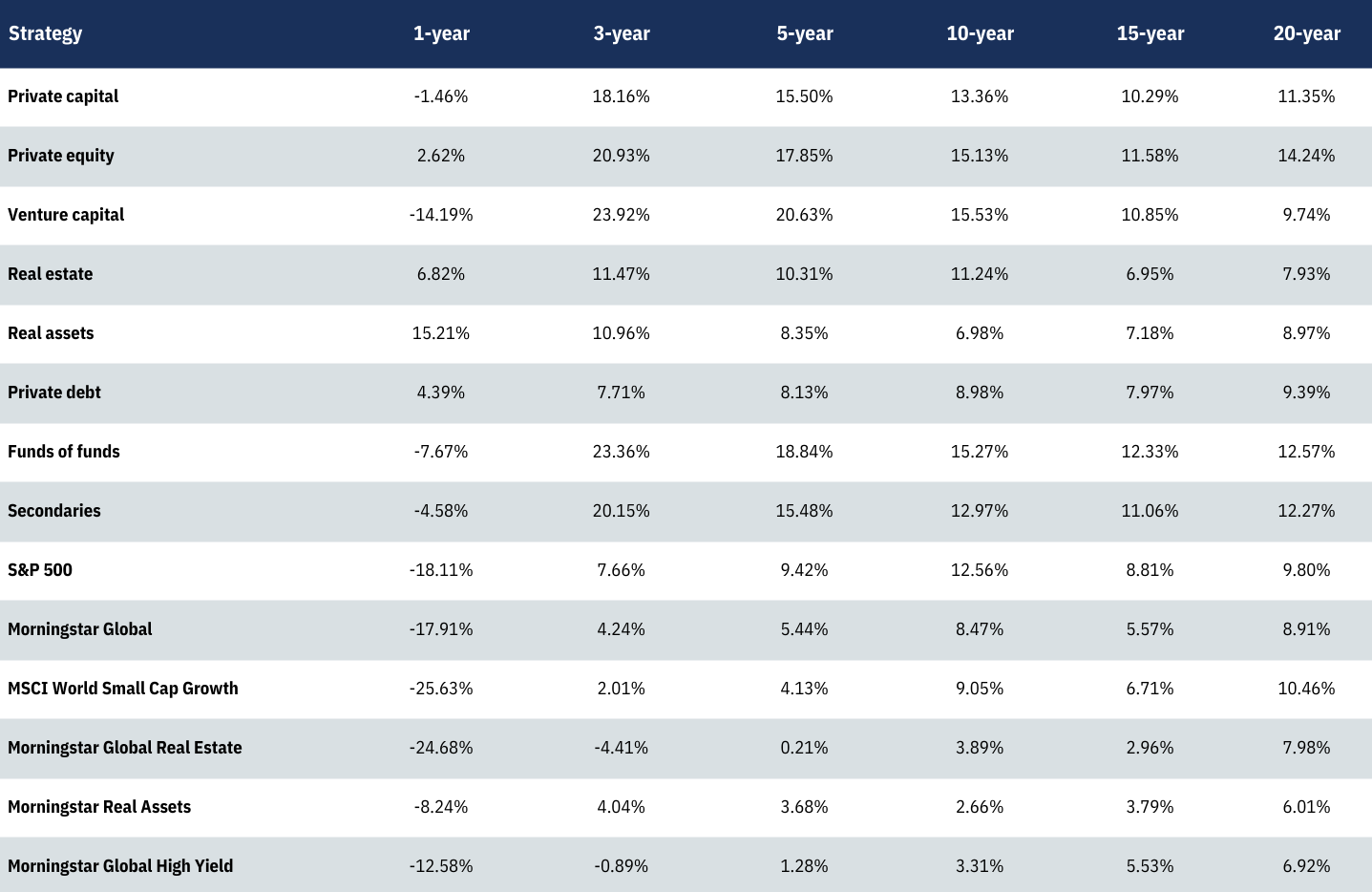

Numerous studies have shown that private market investments have outperformed public equity and bond markets over the long term. As of the end of 2022, PitchBook reports that private equity has has returned 11.6% of the preceding 15-years, compared to 8.8% returns from the S&P500.

PitchBook Q4 2022 Benchmarks

It is important to note, however, that the benefits of private market investments must be balanced against the illiquidity and complexity of these investments. Private market investments are generally illiquid, meaning they cannot be easily sold or traded like public securities. This illiquidity can make it difficult to manage cash flow needs and may require a longer investment horizon. Additionally, private market investments are often complex, with unique risks and challenges that must be carefully considered by financial advisors and their clients.

Types of Private Equity Strategies

Buyout funds

Buyouts are the most recognizable private equity strategy. In a private equity buyout, a firm acquires a controlling stake in a company with the aim of improving its operations and ultimately generating an attractive return on investment. Buyout funds have the potential to outperform public equities, as the GPs have control and seek to improve the operations of portfolio companies. Additionally, private equity funds often have longer holding periods than the average holding period for public equities, allowing for more time for the GP to execute its strategy and generate returns.

LBOs

Leveraged buyouts, commonly referred to as LBOs, represent a type of private equity buyout strategy where a private equity firm purchases a controlling stake in a company by combining both equity and debt financing. The debt portion is typically secured by the assets of the acquired company, while the private equity firm seeks to enhance the operations of the company to generate a return on investment and repay the debt.

The financing structure of LBOs allows private equity firms to potentially achieve high returns, due to the significant leverage involved. By utilizing debt financing, private equity firms can use a relatively smaller amount of equity to acquire substantial stake in the company. This also allows GPs to hold more portfolio companies in funds. Moreover, private equity firms can focus on improving the operations of the acquired company, driving revenue and profitability, and further increasing potential returns.

But LBOs also entail certain risks, including the potential for default if the acquired company is unable to generate enough cash flow to service the debt, and the possibility of operational difficulties that may result in lower returns on investments.

Buy-and-build, also known as platform or add-on investing, is a common LBO strategy in which a GP acquires a “platform” company and subsequently acquires smaller “add-on” companies to expand the platform’s business operations. The goal is to create a larger, more diversified company that can generate greater revenues and achieve operational efficiencies by combining common functions such as sales and marketing, HR, finance, technology etc.

GPs tend to select platform companies with a solid management team, a strong market position, and a proven track record of generating cash flow. In some instances, the GP will replace executive management if there are perceived shortcomings. After acquiring the platform company, the GP will work with the management team to identify and acquire smaller add-on companies that can complement the platform’s existing business. These add-on companies are typically smaller and transact at lower valuations. This allows the GP to “buy-down” the valuation of the combined entity.

However, the buy and build strategy also comes with risks. Acquiring and integrating smaller companies can be complex and time-consuming, and there is always a risk that the acquisitions may not perform as expected. It may be challenging to integrate disparate cultures and create a unified vision. Furthermore, the strategy requires significant capital investment, which may limit the number of potential add-on acquisitions. Typically, add-ons are acquired with material debt financing. If the availability or cost of debt becomes prohibitive, a key value creation initiative may be less attractive.

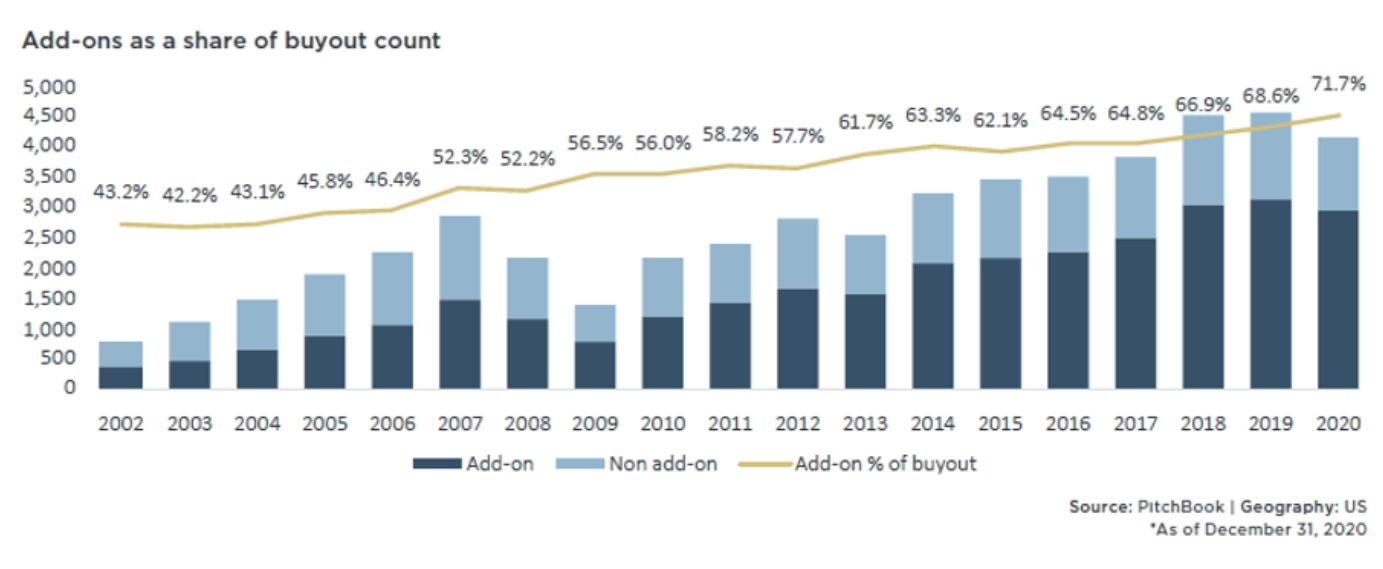

Despite these risks, the buy and build strategy has become increasingly popular in recent years. According to PitchBook, add-on deals accounted for 72% of all private equity deals in 2020, up from 56% in 2010. (1)

GROWTH

Growth strategies are another common private equity strategy. Unlike LBOs that aim for controlling stakes in mature firms, growth private equity focuses on accelerating the growth of dynamic companies by collaborating with existing management and typically not seeking full control. GPs seek to maintain significant influence and may require certain minority shareholder protections.

Targeting younger companies that show strong potential for rapid expansion, growth private equity provides capital along with strategic guidance for scaling operations, entering new markets, or investing in technology and innovation. Rather than relying on financial leverage or add-on acquisitions, as seen in LBOs, growth private equity emphasizes organic growth. This may include product development, geographical expansion, and key personnel hiring to enhance efficiency and drive revenue.

The collaborative nature of these investments often necessitates a robust alignment between the private equity firm and the target company’s management team. This collaboration aims to achieve mutual growth objectives and a shared strategic vision. Like other investment strategies, growth private equity carries risks, including higher exposure to market volatility and competition., Success hinges on the company’s ability to execute its growth plans. However, the potential for high returns is also significant. By investing in high-growth companies at earlier stages, growth private equity firms can realize substantial profits as these firms mature and increase in value.

Venture capital

Venture capital (VC) is a form of private equity investment that is typically made in early-stage companies with high growth potential. The goal of venture capital is to help these companies grow and become successful, which can result in significant returns on investment. There are several stages of venture capital investing, including seed funding, early-stage funding, and growth-stage funding. In the seed stage, venture capital investors provide funding to help a company get off the ground.

In the early-stage, venture capital investors provide funding to help a company grow and develop its products or services. In the growth stage, venture capital investors provide funding to help a company scale and expand its operations.

VC investments are typically structured as convertible preferred structures with liquidation preferences. VCs typically acquire a minority stake, or around 10% or 20%, and take an active role with founder(s). Commonly, VCs take board seats and lever networks for talent, product development, revenue introductions etc. A material portion of a VC fund is typically reserved for follow-on investments in portfolio companies that are matching or exceeding expectations. Compared to other private market options, venture capital is generally thought of as “high risk, high (potential) return.” In a venture capital fund, one or two portfolio companies may represent most of the total return, potentially compensating for many unsuccessful companies.

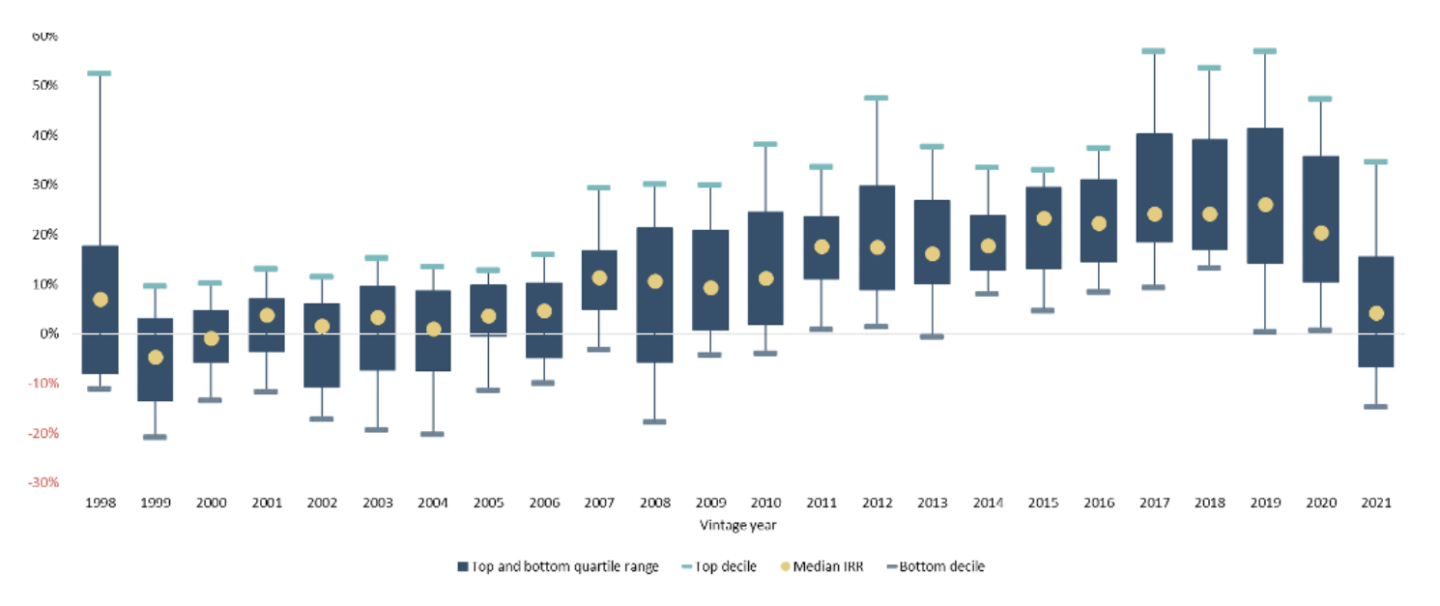

The effect is compounded by the dispersion in returns between top-tier venture capital managers and lower-tier managers. This difference is significant, and it is one of the most striking features of the VC industry.

While top-tier managers have consistently delivered outsized returns, lower-tier managers have struggled to generate positive returns. There are several reasons for this effect, but the most significant is likely top-tier managers’ access to higher quality deal flow. Top-tier managers also have larger and more influential networks and better resources to add value to investments. There could also be a halo effect where prior success begets futures success, especially in attracting dynamic entrepreneurs.

The dispersion in returns between top-tier and lower-tier VC managers has important implications for investors. First, it highlights the importance of selecting the right VC manager. Investors who invest with top-tier managers are more likely to generate outsized returns than those who invest with lower-tier managers. Second, it underscores the need for diversification. Even top-tier managers have portfolio companies that fail, and no single VC manager can consistently generate outsized returns in every investment. Therefore, investors should consider investing with multiple managers to diversify their exposure across different managers, strategies, and geographies.

Source: PitchBook – Geography: North America; Data as of December 31, 2022

Private credit

Private credit refers to the provision of debt financing to companies in the form of loans that are privately held. While most private credit is issued to private companies, private credit has continued to take share in providing financing to public companies as well. Private credit can take many forms: sponsor-backed lending; non-sponsor-backed lending; distressed debt investing; collateralized loan obligations (CLOs); and asset-based lending.

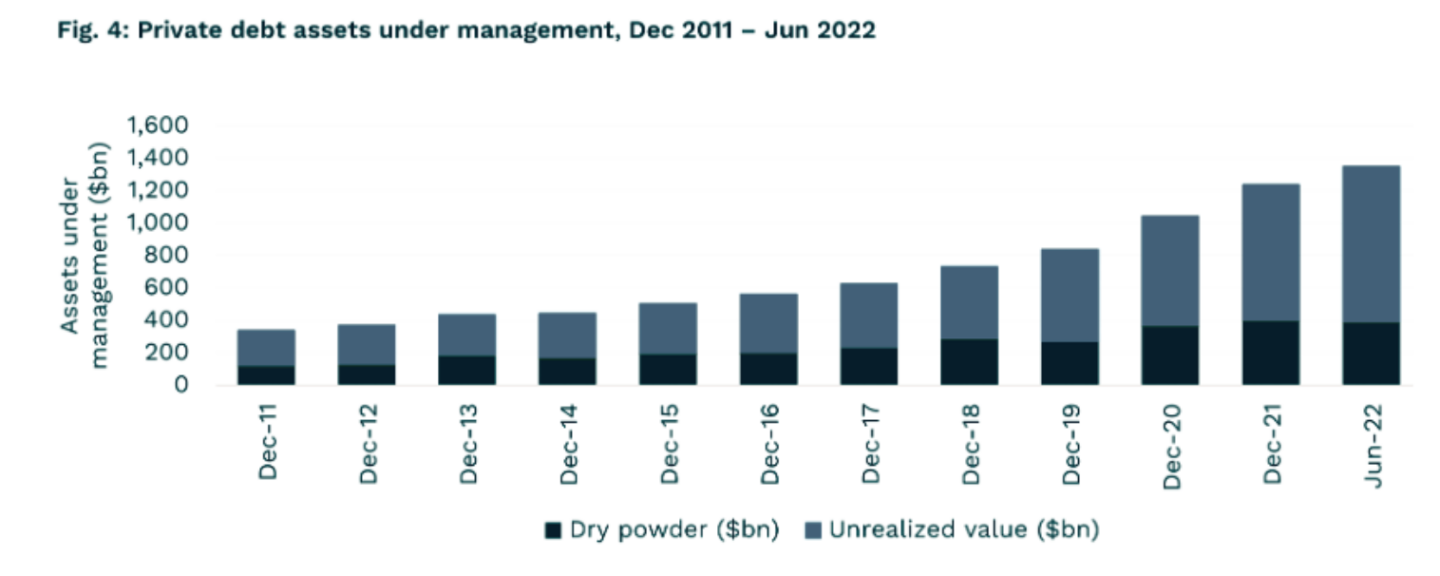

Private credit strategies have become increasingly popular among both institutional and private wealth investors in recent years as they offer the potential for attractive returns with lower volatility than equity investments.

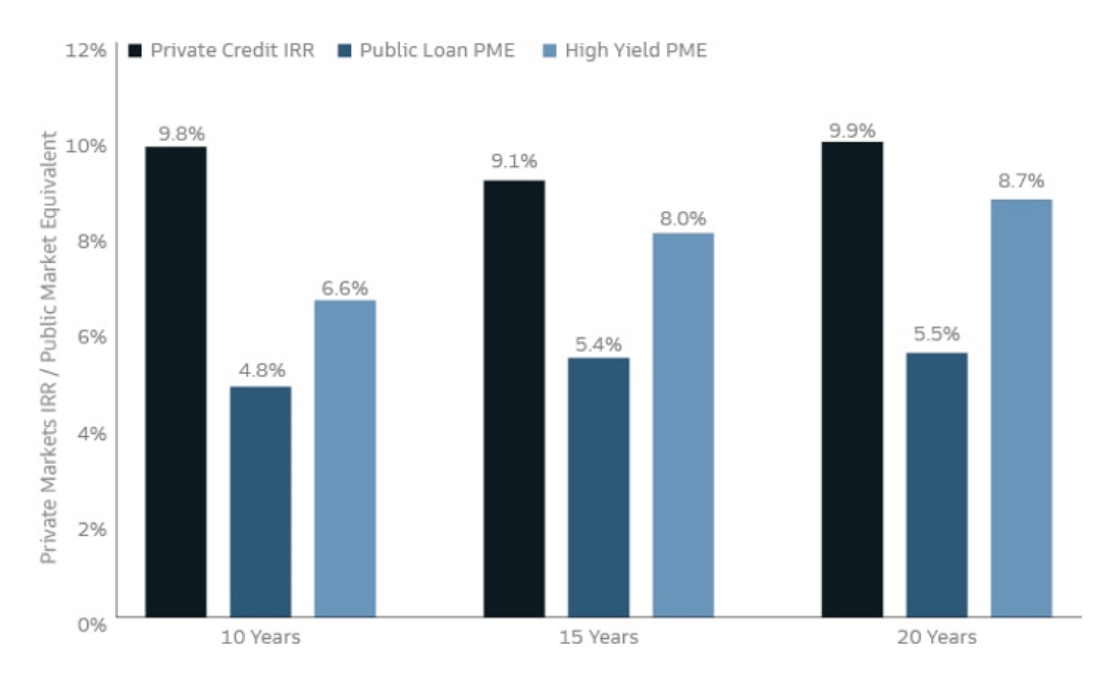

Private credit returns have historically been higher than those of publicly available alternatives such as corporate bonds. According to a report by Goldman Sachs, from 2012-2022, private credit has annualized 10% returns, compared to 5% for public loans.(2)

DIRECT LENDING

Direct lending is a form of private credit in which investors provide debt financing directly to companies. Dedicated direct lending GPs raise capital through an LP structure and utilize LP capital as well as debt capital to originate and structure loans. This can be done through a variety of structures, including senior secured loans, mezzanine debt, and unitranche loans. These terms refer to where the loans reside in the capital structure and the relative claim on assets. Direct lending typically involves making loans to mid-market companies that may not have access to traditional bank financing or public markets.

Direct lending is often categorized as “sponsor-backed” or “non-sponsor-backed.” Sponsor-backed lending is a form of private credit in which investors provide debt financing to companies that are owned or controlled by private equity firms. These companies are often undergoing a significant transformation, such as a merger or acquisition, and require financing to support their growth.

Sponsor-backed lending can be an attractive opportunity for investors, as private equity firms often have a track record of successfully executing these types of transactions. Additionally, sponsors may inject additional capital into the borrower if fundamentals decline.

Non-sponsor-backed lending is a form of private credit in which investors provide debt financing to companies that are not owned or controlled by private equity firms. These companies may be looking to finance a specific project or acquisition or may be seeking working capital to support their ongoing operations. In many instances the amount and structure of debt sought by non-sponsor borrowers is outside of common bank thresholds.

Distressed debt

Distressed debt investing is a form of private credit in which investors provide financing to companies that are experiencing financial distress. Distressed debt investors typically purchase the debt of companies that are in default or bankruptcy and attempt to restructure the company’s operations to improve its financial position. The strategy can also include providing rescue financing to bridge the company through a restructuring or transformative process.

CLOs

A collateralized loan obligation (CLO) is a type of structured credit product. A CLO is a pool of loans that are securitized and sold to investors. The loans in the CLO are typically senior secured loans issued by non-investment grade borrowers in the broadly syndicated market.

The CLO is divided into tranches, with each tranche having a different level of risk and return. The most senior tranche is the safest and has the lowest yield, while the most junior tranche is the riskiest and has the highest yield.

CLOs are created by first incepting a special purpose vehicle (SPV). The SPV issues bonds to investors and uses the proceeds to purchase a pool of loans from a variety of issuers. The loans are typically senior secured loans with a high yield, issued by companies that are below investment grade. The SPV then divides the loans into tranches, which are sold to investors.

Next, the SPV collects the loan payments from the borrowers and uses them to pay the interest and principal payments to the investors in the CLO. The investors receive payments based on the tranche they have invested in. The senior tranche receives payments first, followed by the mezzanine tranches, and then the equity tranche. Inefficiencies can arise in levered loan and CLO markets due to complexity, relative liquidity, restrictions for CLO debt investors on holding securities below a certain rating, and other factors. These inefficiencies can create opportunities for investors as well as higher volatility.

ABL

Asset-based lending (ABL) is a type of lending in which a borrower’s assets are used as collateral for a loan. The assets could be accounts receivable, inventory, equipment, or real estate. ABL is typically used by capital intensive businesses or companies that do not have strong credit profiles and cannot obtain traditional bank loans. Sponsor and non-sponsored direct lending are typically cash flow based lending. ABL strategies can offer diversification given potentially different types of borrowers and sectors.

SECONDARIES

A compelling way to begin investing in private capital is through secondary markets. In these markets, investors buy and sell interests in private equity, credit, or venture funds. Investors in these funds may wish to sell their interests in the funds for a variety of reasons, including a desire to liquidate their holdings, rebalance their portfolio, or free up capital for new investments. Private capital secondaries provide a way for buyers to acquire these interests and gain exposure to a portfolio of private companies or funds.

Investing in private capital secondaries can offer several benefits to investors. First, it provides access to a diversified portfolio of private companies that have already been vetted by experienced private equity managers. This can be especially attractive for investors who lack the resources or expertise to conduct due diligence on individual private funds themselves. Secondaries funds often offer attractive returns, as investors can purchase interests in private equity funds at a discount to their net asset value in exchange for providing liquidity. Finally, because of high levels of diversification within portfolios of secondaries, investors can often expect quicker cash-flows with a less pronounced J-curve. High levels of diversification also result in less dispersion between the highest and lowest performing managers.

Operational Considerations of Private Capital Investing

Although private capital investments offer numerous advantages, they involve significantly greater operational difficulties than conventional investments. One of the key considerations when investing in private capital is fees. Private equity firms typically charge a management fee, usually 1% to 2% of commitments to a fund, as well as a performance fee, commonly referred to as a “carry.” The carry is typically 20% of the profits generated by the investment. Many buyout funds have a preferred return, or a specified return that must be delivered to LPs before the GP can collect incentive fees. Preferred returns are not common in growth or venture strategies. These fees can be higher than those charged by traditional investments such as mutual funds or ETFs.

Another important aspect of private capital investment is the subscription process. The subscription process typically involves an investor completing a lengthy subscription agreement and making a capital commitment to the fund. Investors must prove their identity and provide documentation regarding their activities as prescribed by federal law, often known as AML (anti-money laundering) and KYC (know your customer) requirements. The capital commitment represents the amount of money the investor has agreed to invest in the fund over the investment period, which is typically five to ten years.

Liquidity considerations are also important when investing in private capital. These investments are typically illiquid, meaning they cannot be easily sold or redeemed. The hold period for private capital funds is usually up to ten years or more. Additionally, private capital investments have a “J-curve” effect, meaning that the returns are often negative in the early years of the investment and then increase as the investments mature. This is due to fees being charged on commitments at inception while the GP is calling and investing commitments over an extended period.

Cash flows are also important considerations when investing in private capital. Capital commitments are made upfront, but the private equity firm may make capital calls over the investment period as it identifies investment opportunities. Capital calls have the potential to come during periods of stress in other markets, causing investors to source liquidity at challenging times. Some funds can recycle capital or reinvest previous distributions. Similarly, distributions may be made periodically as investments are sold, and investors typically receive their capital back in stages rather than in a lump sum.

REPORTING

Performance reporting in private capital is typically delayed, with quarterly or annual updates provided to investors. It is important to track performance closely and evaluate it over the long term. This process can assist in assessing the merits of a GP’s subsequent fund. Quantitative metrics for private capital are generally discussed in terms of ratios and IRR. These include DPI, RVPI, TVPI.

DPI stands for distributed to paid-in capital and measures the amount of cash that has been returned to investors relative to the amount of capital they have contributed to the fund. DPI is calculated by dividing the total amount of distributions received by the LPs by the total amount of capital called by the GP. A DPI of 1.0 indicates that all the capital contributed by the LPs has been returned, while a DPI of less than 1.0 indicates that some capital remains invested in the fund.

RVPI stands for residual value to paid-in capital and measures the unrealized value of the remaining portfolio companies in the fund relative to the amount of capital that has been called by the GP. RVPI is calculated by dividing the total value of the remaining portfolio companies by the total amount of capital called by the GP. RVPI provides insight into the potential value that may be realized by the fund in the future.

TVPI stands for total value to paid-in capital and combines both DPI and RVPI to provide a comprehensive measure of the total value that has been realized and the potential value that may be realized by the fund. TVPI is calculated by adding DPI and RVPI. A TVPI of greater than 1.0 indicates that the fund has generated a positive return for investors, while a TVPI of less than 1.0 indicates that the fund has generated a negative return.

Another common metric is the internal rate of return, or IRR. A fund’s IRR is its annualized rate of return, considering both the magnitude and timing of cash flows. IRR is calculated by solving for the discount rate that equates the present value of the cash inflows to the present value of the cash outflows. In other words, it is the discount rate at which the net present value of the investment equals zero. Expressed as a percentage, IRR is often used to compare the performance of different private equity investments and can be used to compare private capital performance to public market equivalents. There are key differences between an IRR metric and time-weighted return, which most public investments report. The IRR is dollar-weighted and assumes cash flows received are reinvested at the calculated IRR. Reinvesting distributions at a similar IRR may be challenging for investors.

TAXES

Tax considerations are also important when investing in private capital. Investors typically receive a K-1 tax form from most private fund structures, which details their share of the income, deductions, and credits from the investment.

It is important to understand the tax implications of private capital investments, particularly for investors who hold these investments in taxable accounts. In many instances, a GP does not issue a final K-1 until well after April 15th, requiring LPs to file taxes on extension. It can also be cumbersome for LPs who hold an extensive portfolio of private funds, as each fund will issue their own tax forms.

CONCLUSION

Overall, private capital investments provide a compelling opportunity for investors to diversify out of public markets and seek advantages that they may not otherwise have access to through traditional means. Although investors must be aware of issues unique to private capital investing, including potential risks and operational hurdles, private capital can serve an important role in an investor’s portfolio as a potential for diversification and risk enhancement.

Download a PDF version of the report here.

SOURCES

(1) Springer, R. (2021). Exploring Trends in Add-On Acquisitions. Pitchbook.

(2) https://www.gsam.com/content/gsam/us/en/advisors/market-insights/gsam-insights/2022/understanding-private-credit.html

DISCLAIMER

This report and the information contained herein is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, an invitation, inducement, offer

or solicitation to engage in any investment activity. This information is for discussion purposes only. Nothing contained in this report constitutes tax nor legal advice. Alternative Investing is complex and speculative; and thus, not suitable for all investors. Such investment vehicles contain a high degree of risk and therefore no assurance may be made that any alternative investment objectives will be attained nor that investors will receive return of capital.

This report is an opinion only; it is not to be relied upon as the basis for an investment. Any data and firm information shown are for illustrative purposes. The information in this report has been provided to GLASfunds, including its employees, by sources determined to be reliable in providing such information. Therefore, GLASfunds has not, and is unable to, independently review, prepare, or verify information contained herein; further, GLASfunds makes no representation or warranty regarding the accuracy of the information provided to GLASfunds.Past performance is not indicative of future returns.

GLASfunds, LLC is a registered investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, as amended. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training.